Originally published in the January/February 2025 issue of Bench & Bar of Minnesota Environmental Law Update, Minnesota State Bar Association.

Part one of this article (“Planet PFAS: Laws, litigation, and the battles over forever chemicals,” B&B 12/24), focused on the increasing volume of litigation of all types surrounding per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Paralleling this increase in litigation is an evolving regulatory regime that is in part based on existing environmental statutes and liabilities, and in part all its own. A PFAS regulatory regime targeted at removing PFAS from products, air, water, and waste to prevent new PFAS pollution, managing PFAS when pollution has occurred, and cleaning up PFAS at particularly contaminated sites continues to be developed in Minnesota and at the federal level and is expected to increase (at least at the state level) in the years to come.

The lodestar for PFAS regulation in Minnesota is a near-200-page document released in February 2021 by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA), along with the Departments of Health, Natural Resources, and Agriculture. Entitled Minnesota’s PFAS Blueprint,1 it outlines a three-part high-level strategy for PFAS management:

- Prevent PFAS pollution wherever possible.

- Manage PFAS pollution when prevention is not feasible or pollution has already occurred.

- Clean up PFAS pollution at contaminated sites.

In 2022, MPCA established a plan to encourage voluntary PFAS monitoring at numerous public and private facilities across the state.2 Targeted facilities include those that may be sources of PFAS pollution and those that may be conduits of PFAS into the environment. The plan involves various regulatory programs, including air, wastewater, solid and hazardous waste, industrial stormwater, and remediation, tailoring the type of PFAS monitoring to the waste streams involved.

Notably, MPCA’s plan does not address all 5,000-plus PFAS chemicals. Rather, the specific PFAS monitored vary by the analytical methods MPCA has approved, with many methods addressing between 20 to 40 PFAS.

While Minnesota’s PFAS blueprint and guidance documents have set the foundation for a widespread PFAS environmental regulatory framework, the Minnesota Legislature, in its 2023 session, expanded on previous legislation to pass a new law aimed at reducing the amount of PFAS in everyday products.

It was not the first time Minnesota adopted laws intended to ban or control PFAS in certain products. In 2019, the Legislature created Minn. Stat. §325F.072,3 which prohibited the use of Class B firefighting foam that included intentionally added PFAS for most testing or training purposes after July 1, 2020.4 The Legislature amended section 325F.072 in 20235 to include a ban on all uses of such foam and a ban on manufacturing or knowingly selling, offering for sale, distributing for sale, or distributing the foam for use in Minnesota, effective January 1, 2024, with some limited exceptions.6

In 2021, the Legislature prohibited the manufacture or the knowing sale, offer for sale, distribution for sale, distribution, or offer for use in Minnesota of any food package that contains intentionally added PFAS, also effective January 1, 2024.7 “Food packaging” under the law means “a container applied to or providing a means to market, protect, handle, deliver, serve, contain, or store a food or beverage,” while “intentionally added” means “PFAS deliberately added during the manufacture of a product where the continued presence of PFAS is desired in the final package or packaging component to perform a specific function.”8 To assist in enforcing this ban, the MPCA commissioner may require any person to furnish her any information that is relevant to show compliance with this ban.9

The Minnesota Legislature Expands PFAS Regulation

The Legislature passed a number of new environmental laws in 2023. They included measures governing air toxics regulations and emissions reporting, odor management, and cumulative impacts/environmental justice. The 2023 environmental law with perhaps the highest profile, however, was “Amara’s Law,”10 codified at Minn. Stat. §116.943. It was named after Amara Strande, the young woman from the East Metro who died just before the law’s passage from a cancer that she and her family believed was related to PFAS contamination in that area.

Products

Minn. Stat. §116.943 contains the most extensive efforts to date to regulate PFAS in products sold or used in Minnesota, with a focus on preventing exposure to PFAS.

*SS*Product bans beginning this year: As of January 1, 2025, 11 categories of products cannot be sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in Minnesota if the products contain intentionally added PFAS.11 The categories include carpets or rugs, cleaning products, cookware, cosmetics, dental floss, fabric treatments, juvenile products, menstruation products, textile furnishings, ski wax, and upholstered furniture.

*SS*Future product bans: The MPCA commissioner, between January 1, 2025, and January 1, 2032, may identify additional products by category or use that may not be sold, offered for sale, or distributed for sale in Minnesota.12 Regardless of whether she does so, beginning January 1, 2032, no person may sell, offer for sale, or distribute for sale any product with intentionally added PFAS within Minnesota, unless the commissioner has determined by rule that the use of PFAS in the product is “currently unavoidable.”13 “Currently unavoidable use” means “a use of PFAS that the commissioner has determined by rule under this section to be essential for health, safety, or the functioning of society and for which alternatives are not reasonably available.”14 This exemption does not apply to the products banned as of January 1, 2025.15

Products with intentionally added PFAS that do not fall within the 11 currently banned categories still face upcoming regulatory requirements. Beginning no later than January 1, 2026, every manufacturer who wishes to sell, offer for sale, or distribute for sale a product with intentionally added PFAS that is not already subject to the 2025 ban must provide certain information on the product and its PFAS content to the MPCA commissioner.16 Manufacturers have an ongoing obligation after that date to update or provide anew the above information on any product to be sold, offered for sale, or distributed within Minnesota.17 Failure to provide the requisite information by January 1, 2026, means the product cannot be sold, etc., in Minnesota after that date until the commissioner receives the requisite information.18 But the commissioner has the ability to alter the deadline for information submission, under certain circumstances.19

The commissioner may direct a product manufacturer to provide her with test results showing the amount of each PFAS in a product sold, offered for sale, or distributed in the state if she believes the product contains intentionally added PFAS.20 The manufacturer must then provide the test results to the commissioner and either certify the product does not contain intentionally added PFAS or, if it does, provide relevant information, including the above product information.21

Manufacturers must notify persons who sell or offer for sale a product that has been banned in Minnesota — including products banned because information has not been provided to the commissioner — that sale of that product is prohibited in the state and then provide the commissioner with a list of the names and addresses of those notified.22

The commissioner has the power to adopt rules necessary to implement Minn. Stat. §116.943 and the power to establish a fee payable by a manufacturer upon submission of the above-described information to cover the MPCA’s costs of implementing the new statute.23 The commissioner also has the power to compel a person to furnish her with any information the person may have or may reasonably obtain that is relevant to showing compliance.24

Since section 116.943’s creation, the MPCA has sought and received comments on potential rules regarding fees, reporting requirements, and the definition of “currently unavoidable use.” Its rulemaking work continues as of this publication.

Regulating PFAS in Fertilizers and Pesticides

Section 116.943 is not the only statute created in 2023 that regulates products with intentionally added PFAS. Minn. Stat. §§ 18B.26 and 18C.202 include information submission requirements and prohibitions similar to those regarding products under section 116.943 but pertaining to pesticides and fertilizers, respectively. Beginning January 1, 2026, pesticide registrants and fertilizer manufacturers must provide annual statements to the Commissioner of Agriculture that a given pesticide or fertilizer contains no intentionally added PFAS or, if it does, to include in the statement certain information required under the statutes.25 The commissioner in both cases also may extend the deadline for the submission of the information under certain circumstances.26

Both statutes also have product bans that mirror those under the MPCA’s statute. Beginning January 1, 2032, the Agriculture commissioner may not register a pesticide or fertilizer product containing intentionally added PFAS for use in Minnesota unless the commissioner determines the use of PFAS in the product is currently unavoidable.27 Even before that, the commissioner may not register a cleaning product beginning January 1, 2026, if the product contains intentionally added PFAS unless the commissioner determines the use of PFAS is a currently unavoidable.28

PFAS Requirements Under TSCA

The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) gives the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authority to require reporting, recordkeeping, and testing related to chemical substances and/or mixtures. The EPA finalized rules under TSCA that impose recordkeeping and reporting requirements for PFAS or PFAS-containing articles retrospectively, for any year since January 1, 2011. Under the rule, manufacturers and importers (but not distributors or retailers) are required to report all PFAS manufacturing, including the manufacture of articles containing PFAS. Originally, reporting was scheduled to begin in November 2024, but the EPA delayed the start of the reporting period until July 2025.

The TSCA reporting requirement defines PFAS based on its chemical structure, meaning the rule may apply to newly developed PFAS that are not included in other rules. Furthermore, TSCA’s definition of the key term “article” is expansive, meaning a manufactured item that:

(1) is formed to a specific shape or design during manufacture;

(2) has end use function(s) depending in whole or in part upon its shape or design during end use; and

(3) has either no change of chemical composition during its end use or only those changes of composition which have no commercial purpose separate from that of the article, and that result from a chemical reaction that occurs upon end use of other chemical substances, mixtures, or articles; except that fluids and particles are not considered articles regardless of shape or design.29

There are some exclusions; however, the scope of the rule is immense, and manufacturers and importers of PFAS, or products that contain PFAS, should consider whether the TSCA reporting requirement applies to them.

Managing PFAS in Drinking Water

One of the primary concerns regarding PFAS has been the potential health impacts of PFAS in public drinking water systems. PFAS went largely unregulated in United States drinking water systems until Spring 2024, when EPA took an initial, but important, step to begin regulating PFAS in drinking water.

On April 10, 2024, the EPA issued a final rule establishing National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) for PFAS chemicals for the first time.30 The new regulations will have significant ramifications for drinking-water providers and other regulated parties.

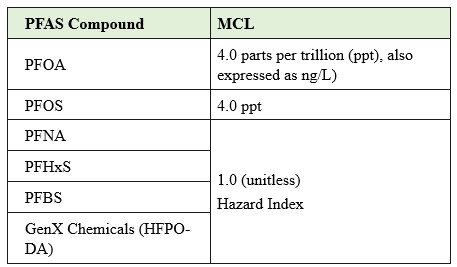

The EPA enacted this rule under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA),31 which authorizes the agency to set drinking water standards that must be met by any public water system. “Public water systems” include not only municipal drinking water plants but also localized facilities that may have their own drinking water systems, such as schools, factories, office buildings, campgrounds, or hospitals. Drinking water standards under the SDWA include enforceable maximum contaminant levels (MCLs), which represent the “maximum permissible level of a contaminant in water which is delivered to any user of a public water system.”32 EPA’s PFAS MCLs in the new regulations are as follows:

Public water systems have five years to comply with the MCLs. In addition to establishing these standards, EPA’s final rule imposes other requirements on public water system operators, including (a) PFAS monitoring requirements, (b) a requirement to notify the public if monitoring detects PFAS levels that exceed the MCLs after 2029, and (c) a requirement for public water systems to install PFAS treatment systems or take other actions to reduce the levels of these PFAS if they exceed the MCLs.

The ramifications of the new PFAS MCLs will be felt most keenly by municipal and other operators of public water systems because of the extreme costs of PFAS-removal treatment. In addition, the new MCLs are likely to have ramifications beyond public water systems. The language of Minn. R. 7050.0221, for example, suggests the new PFAS MCLs will constitute Class 1 water quality standards in Minnesota, meaning they could be potentially translated into water discharge permit limits. Further, MCLs are often used as “applicable or relevant and appropriate requirements” in Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and state remedial action plans for impacted groundwater or surface waters, meaning that at least some cleanups could be required to attain the PFAS MCLs.

Managing PFAS in Wastewater

A separate concern regarding the impact of PFAS on water quality arises from the fact that large amounts of PFAS enter rivers and groundwater daily via the discharge of wastewater — or the land application of wastewater sludge — by publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) and industrial or other facilities. The primary federal regulatory mechanism for controlling pollutants in wastewater is the Clean Water Act’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program.33 Currently, there are limited means of controlling PFAS discharges under the NPDES permit program. But things are beginning to change, at both the federal and state level.

Under the Clean Water Act (CWA), an NPDES permit must be obtained before any pollutant is added from a point source to “waters of the United States,” a category that includes most rivers and lakes.34 NPDES permitting programs are typically implemented by authorized state agencies. The primary way the NPDES program controls pollutants is by requiring the permit to include “effluent limitations” that prescribe the conditions under which the facility can discharge pollutants into the receiving water body. Effluent limitations take one of two forms. The first are water quality-based effluent limits (sometimes referred to as WQBELs), which are set at levels calculated to ensure that the receiving water will meet all applicable state water quality standards. The second are technology-based “effluent limitations guidelines” or ELGs (alternately referred to as “technology-based effluent limitations,” or TBELs), which specify the attainable effluent pollutant reduction based on performance of the best available pollution control technologies within each industrial point source category.

There are currently no ELGs for PFAS. But over the last few years, EPA has been taking steps to include PFAS in ELGs. Most recently, in January 2023, EPA released its biennial Effluent Limitations Guidelines (ELGs) Plan 15, which announced that the agency will initiate rulemaking to revise the ELGs and pretreatment standards for landfill leachate and undertake further studies of discharges from textile mills, POTWs, and concentrated animal feeding operations.35

EPA Memo on Immediate Wastewater Steps

Faced with the current lack of PFAS ELGs, as well as the paucity of state water quality standards for PFAS that could form the basis of WQBELs, EPA has issued guidance to EPA regions and to states on ways they can immediately exercise their existing authority under the CWA to limit PFAS in wastewater discharges. The guidance is set forth in a December 5, 2022, memorandum from EPA Assistant Administrator Radhika Fox entitled “Addressing PFAS Discharges in NPDES Permits and Through the Pretreatment Program and Monitoring Programs.”36 Fox’s memorandum recommends requiring monitoring and best management practices (BMPs) in NPDES permits (including those regulating industrial stormwater) to track and control PFAS. The memorandum also suggests two ways states can still include PFAS effluent limits in permits, even in the absence of published ELGs with PFAS standards: (1) Establish case-by-case TBELs for PFAS dischargers based on “best professional judgment” under 40 CFR 122.44(a), 125.3; and (2) establish WQBELs for PFAS if the relevant state has an applicable PFAS water quality standard (few currently do). Finally, the Fox memo includes recommendations for POTWs on methods to monitor and limit PFAS discharges to the POTW.

MPCA’s PFAS Site-Specific Standards

At the state level, MPCA took significant steps toward establishing PFAS water quality standards in 2020 and 2023 when it created site-specific water quality standards for six PFAS, which apply in certain Twin Cities-area water bodies with elevated levels of PFAS.37 Facilities that discharge to these water bodies must evaluate whether PFAS levels in their wastewater will cause or contribute to a violation of the PFAS water quality standards; if so, their NPDES permits will requires a PFAS effluent limitation.38

Cleanup: PFAS and Property Contamination

Perhaps the most highly anticipated recent PFAS regulation was the May 8, 2024, EPA final rule designating for the first time two PFAS chemicals — perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), along with their salts (i.e., their solids) and structural isomers (i.e., their relevant variants) — as “hazardous substances” under CERCLA.39 CERCLA, also known as the Superfund law, is a powerful federal statute that gives the U.S. government authority to respond to releases of “hazardous substances” into the environment and to obtain reimbursement from “potentially responsible parties” (PRPs), such as current and former property owners, whom CERCLA makes strictly liable for the response costs. CERCLA and its state equivalents, such as the Minnesota Environmental Resource and Liability Act (MERLA), drive remediation and redevelopment of contaminated property across the country and expose many businesses and individuals to potentially devastating financial liability.

By listing PFOA and PFOS as “hazardous substances” under CERCLA, EPA has provided regulators increased authority to order cleanups and to recover costs for PFAS contamination.40 EPA can now address PFOA and PFOS releases via response actions without first establishing that the release may present an imminent and substantial danger.41 Additionally, EPA may seek to recover its costs from the potentially responsible parties (PRPs) in a subsequent cost-recovery action, compel PRPs to perform the cleanup themselves through either administrative or judicial proceedings, or enter into a settlement with PRPs to perform all or portions of the work.42 In addition to direct EPA enforcement actions, the PFOA and PFOS designations may also spur private party cost recovery and contribution actions and claims for natural resource damages (NRD).43

In addition to imposing liability, CERCLA includes reporting requirements.44 In the short term, EPA considers release reporting under CERCLA, as well as Section 304 of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, to be the only direct effects of the designation.45 Under the new CERCLA rule, facilities will be required to report to relevant governmental authorities, within 24 hours, releases of PFOA and PFOS that meet or exceed the reportable quantity (RQ), which is set at one pound — lower than the RQ for many other CERCLA hazardous substances.46

Simultaneously with EPA’s designation of PFOS and PFOA as CERCLA “hazardous substances,” EPA also issued a separate CERCLA enforcement discretion policy, which states that EPA will focus its enforcement authority on parties that significantly caused PFAS releases and will not seek response actions or costs from “passive receivers” of PFAS, such as farmers, municipal landfills, water utilities, municipal airports, and local fire departments.47 Entities such as these otherwise could become subject to burdensome response costs under CERCLA’s strict, retroactive, and joint-and-several liability scheme. This approach is discretionary, however; legislative changes to CERCLA — which are not guaranteed — will likely be necessary to give passive receivers real relief.

PFAS Under MERLA

MERLA is Minnesota’s state-law counterpart to CERCLA.48 While Minnesota has not undertaken formal rulemaking, the MPCA has indicated in guidance documents that it considers PFAS to be MERLA “hazardous substances.”49

MPCA has published a detailed “PFAS Remediation Guidance,” which provides instructions for addressing PFAS contamination in five lifecycle stages and four cross-cutting areas.50 For each of the lifecycle stages — initial site review, site investigation, risk assessment, remediation, and site closure — and cross-cutting areas — brownfields, disposal, communications, and environmental justice — MPCA has created a standalone guidance document.

PFAS and Community Right-to-Know Laws

The federal Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) is designed to help local communities protect public health, safety, and the environment from chemical hazards.51 States are required to appoint a state emergency response commission (SERC), which then divides the state into emergency planning districts with local emergency planning committees (LEPC) — often consisting of fire fighters and health officials, among others — to ensure that EPCRA’s emergency planning measures are implemented.

A cornerstone of these emergency planning measures is toxic release inventory (TRI) reporting, which requires certain facilities that manufacture, process, or otherwise use certain toxic chemicals above specified thresholds to annually report information regarding the chemicals’ presence at their facilities. For the close to 200 PFAS subject to TRI reporting, the minimum reporting threshold is 100 pounds, as compared to the typical threshold of 10,000 pounds.52

Notably, for reporting year 2024, EPA has categorized PFAS as chemicals of special concern.53 This means the TRI de minimis exemption — which allows facilities to exclude small concentrations in mixtures or other trade name products when making threshold determination and release and other waste management calculations — will no longer apply to PFAS.54 Other potential exemptions continue to apply, however, such as exemptions for PFAS that are present in products used for routine janitorial maintenance, personal use by employees, or in process water and non-contact cooling water.55

EPCRA also requires supplier notification to customers of the presence of TRI chemicals in certain products. A supplier that falls within an industrial classification that manufactures (including importing) or processes a TRI-listed PFAS must provide notice when it sells or otherwise distributes a mixture or other trade name product containing the TRI-listed PFAS to a covered facility (or a facility that then may sell or otherwise distribute the product to a covered facility).56 As with the TRI reporting, the de minimis exemption no longer applies to PFAS notifications starting in reporting year 2024.

More PFAS will be added to the TRI chemical list if: (1) EPA finalizes a toxicity value for a PFAS; (2) EPA issues certain significant new use rules (SNURs) under TSCA for a PFAS or adds a PFAS to certain existing SNURs; or (3) EPA adds a PFAS as an active chemical on the TSCA inventory.57 This has resulted in additions of PFAS to the TRI chemical list in reporting years 2023 and 2024, with more likely in the coming years.

PFAS and Air Quality

Regulation of PFAS in air emissions is in its infancy. But there are a few key state and federal developments to be aware of. For example, EPA recently requested comments on whether PFAS should be considered “hazardous air pollutants” (HAPs), which would in turn require them to be reported under the agency’s air emissions reporting rule (AERR).58 EPA had yet to act on this proposal at the time of publication.

Regardless of what happens at the federal level, certain facilities in Minnesota will be required to include some PFAS in their annual air toxics emissions reports to MPCA under a new statute adopted in 2023. Subject to limited exceptions, Minn. Stat. §116.062(c)(2) requires a facility (a) with an air emissions permit and (b) located in Anoka, Carver, Dakota, Hennepin, Ramsey, Scott, or Washington counties to “annually report the facility's air toxics emissions to the agency,” including chemicals (including PFAS) the site reports under the TRI. On November 25, 2024, the MPCA issued its “Notice of Intent to Adopt” proposed rules promulgated pursuant to this authority, which were available for public comment until January 15, 2025.59

Conclusion

Even the most extensive summary of the current state of PFAS regulation can only capture a moment in time. The upcoming federal administration change and the inevitable challenges Minnesota will face as it implements its aggressive regulatory regime will require those affected by these regulations to pay close attention to this evolution and, of course, to seek legal assistance as they navigate this challenging path.

Sidebars

Sidebar 1:

HED: Maine: A cautionary tale?

Minnesota is not the first state to attempt sweeping regulations of PFAS in products. In 2021, Maine passed legislation with registration and prohibitions that Minnesota would later use as a model for its own legislation. Among other things, Maine’s 2021 legislation prohibited the sale or distribution of products with intentionally added PFAS after January 1, 2023, unless the manufacturer submitted information on those products to the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) by that date. The 2021 legislation also established future bans for certain product categories and amended the state’s definition of “hazardous substance” to include any substance designated as such under CERCLA.

Implementation of the new requirements did not go smoothly. DEP, for instance, had to grant reporting deadline extensions to more than 2,500 manufacturers when DEP failed to promulgate regulations to govern the information submission process by the January 1, 2023, reporting deadline. In response, Maine amended its legislation in 2023 to extend the official reporting deadline to January 1, 2025, and to further clarify its “currently unavoidable use” exemption. When even that new deadline became unworkable, Maine dropped the reporting requirement altogether in April 2024. The amended statute (38 MRSA § 1614) still contains a number of product category bans that began in 2023 and will continue to roll out in stages until January 1, 2032. At that time, as in Minnesota, all products with intentionally added PFAS will be prohibited from sale or distribution in the state unless the PFAS in a product is determined to have a “currently unavoidable use.”

MPCA staff, in a July 2024 webinar, said the agency was planning to base Minnesota’s reporting system on the existing High Priority Chemicals Data System model that is part of the Interstate Chemicals Clearinghouse (ICC). It is worth noting that DEP also worked with the ICC as it sought to develop Maine’s (ultimately unsuccessful) reporting system. All eyes are now on Minnesota to see if it is any more successful in implementing its own system by January 1 of next year.

Sidebar 2:

HED: Addressing PFAS in transactions

The allocation and mitigation of PFAS risks in transactions is not unlike the allocation and mitigation of other environmental risks, with certain PFAS-specific considerations to be aware of. As with all transactions, the nature of the deal (such as stock deal, asset deal, or acquisition of real property) and the client’s risk tolerance can affect the strategy. When a transaction presents potential PFAS concerns, practitioners should consider, among other things, the following factors:

- Does the definition of “hazardous substances” or “hazardous materials” in the transaction documents clearly include PFAS?

- If the parties are relying on insurance (such as pollution legal liability insurance or representations and warranties insurance) as a risk management tool, do the insurance policies cover PFAS? If PFAS is a policy exclusion, what is the scope of the exclusion?

- If indemnification is being relied upon as a risk management tool, has the creditworthiness of the indemnitor been vetted, and is it sufficient to back the potential liabilities related to PFAS in an evolving regulatory landscape?

- What federal or state liability protections are available, and have the parties taken the necessary steps to establish such liability protections?

Citations

1 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, Minnesota’s PFAS Blueprint (2022), https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air-water-land-climate/minnesotas-pfas-blueprint .

2 Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, Monitoring PFAS (2022), https://www.pca.state.mn.us/air-water-land-climate/monitoring-pfas .

3 2019 c 47 s 2, codified at Minn. Stat. §325F.071 (2019).

4 Minn. Stat. §325F.072, subd. 3 (2022).

5 2023 c 60 art 3 s 25 – 27, codified at §325F.072, subdivision 1,

6 Minn. Stat. §325F.072, subd. 3(a) (2024).

7 1Sp2021 c 6 art 2 s 105, codified at Minn. Stat. § 325F.075 (2024).

8 Minn. Stat. §325F.075, subd. 1(b), (d) (2024).

9 Id., subd. 3(b).

10 2023 c 60 art 3 s 21. See also Minn. Stat. § 116.943, subd. 10 (giving short title of new section as “Amara’s Law.”

11 Minn. Stat. §116.943, subd. 5(a).

12 Minn. Stat. §116.943, subd. 5(b).

13 Id., subd. 5(c).

14 Id., subd. 1(j).

15 Id.

16 Id., subd. 2(a).

17 Id., subd. 2(c).

18 Id., subd. 2(d).

19 Id., subd. 3.

20 Id., subd. 4(a).

21 Id., subd. 4(b) and (c).

22 Id., subd. 4(d).

23 Id., subds. 6 and 9.

24 Id., subd. 7(b).

25 Minn. Stat. §§18B.26, subd. 7(a), 18C.202, subd. 1.

26 Id.

27 Minn. Stat. §§18B.26, subd. 8(b), 18C.202, subd. 3.

28 Minn. Stat. §§18B.26, subd. 8(a), 18C.202, subd. 3.

29 40 C.F.R. § 705.3.

30 See Pre-Publication Version, 40 C.F.R. pts. 141 & 142.

31 42 U.S.C. §300f et seq.

32 42 U.S.C. §300f (3).

33 See 33 U.S.C. §1342.

34 33 U.S.C. §1311(a).

35 EPA has also begun taking steps that will facilitate WQBELs in NPDES permits. For example, in October 2024, EPA finalized national ambient water quality criteria for the protection of aquatic life — values often used by states in setting water quality standard s— for PFOA and PFOS. See 89 Fed. Reg. 81077 (10/7/2024). EPA subsequently issued draft water quality criteria for the protection of human health for PFOA, PFOS, and PFBS. See 89 Fed. Reg. 105041 (12/26/2024).

36 https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-12/NPDES_PFAS_State%20Memo_December_2022.pdf

37 Notably, among the discharges to Pool 2 of the Mississippi is 3M’s Cottage Grove facility, and MPCA has utilized the site-specific standard, along with other legal bases, to propose PFAS-related permit conditions in 3M’s draft reissued NPDES permit. For more information on the draft NPDES permit, see Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, Cottage Grove 3M Chemical Operations, https://www.pca.state.mn.us/local-sites-and-projects/cottage-grove-3m-chemical-operations.

38 See 40 C.F.R. §122.44(d)(1)(i).

39 See 89 Fed. Reg. 39124 (5/8/2024).

40 Notably this is EPA’s first-ever use of section 102(a) of CERCLA to add substances to the existing statutory list of hazardous substances via rulemaking.

41 See 89 Fed. Reg. at 39151 and 42 U.S.C. §9604.

42 See id. and §§9606, 9607.

43 See id., §9613.

44 42 U.S.C. §9603.

45 89 Fed. Reg. at 39131-32.

46 40 C.F.R. part 302, Table 302.4.

47 https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/pfas-enforcement-discretion-settlement-policy-cercla.pdf

48 Minn. Stat. ch. 115B.

49 See, e.g., MPCA, “Frequently asked questions on the PFAS Monitoring Plan” (explaining that “the agency considers PFAS ‘hazardous substances’ under MERLA”), available at https://www.pca.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/p-gen1-22f.pdf.

50 See MPCA, “PFAS Remediation Guidance,” available at https://www.pca.state.mn.us/business-with-us/pfas-remediation-guidance.

51 See 42 U.S.C. ch. 116.

52 See 42 U.S.C. §11023; 40 C.F.R. §372.22; 40 C.F.R. §372.28; 40 C.F.R. §372.65(d).

53 88 Fed. Reg. 74360 (10/31/2023).

54 Id. at 74362.

55 See 40 C.F.R. §372.38.

56 40 C.F.R. §372.45.

57 National Defense Authorization Act §7321(c) (2019).

58 See 88 FR 54118, 54148 (8/9/2023).

59 49 SR 563 (11/25/2024).